It’s a modern tragedy in miniature. Your phone, an essential lifeline to your world, slips from your grasp. You pick it up to see the spiderweb crack across the screen. You take it to a repair shop and are met with a staggering quote, often hundreds of dollars, and the familiar advice: “You might as well just get a new one.”

For years, we’ve accepted this as normal. But what if it isn’t? What if the difficulty and expense of fixing the things we own isn’t an accident, but a deliberate design?

This is the central question behind the growing global “Right to Repair” movement—a powerful pushback from consumers, independent repair shops, and even farmers against a system that has made us renters of our own technology. It’s a fight about who truly owns the products we buy, and it’s starting to tip the balance of power back to you.

The Problem: How Repairs Became So Difficult

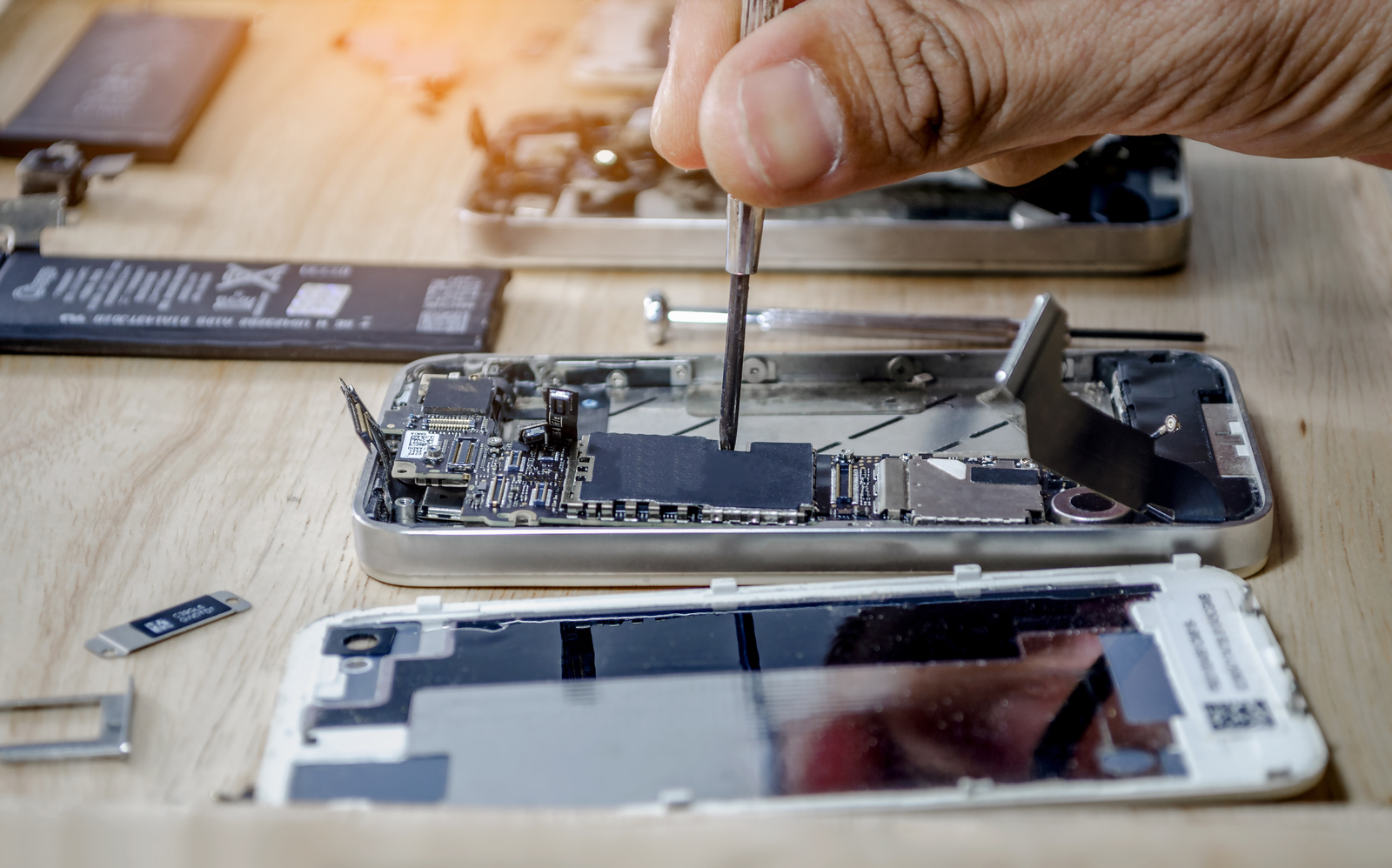

The reason your phone is so hard to fix often comes down to tactics designed to create a repair monopoly.

- Proprietary Parts: Manufacturers use custom-designed screws that require special tools, glue batteries and screens into place making them difficult to remove, and design components that are incompatible with any other model.

- “Part Paring”: This is the most frustrating tactic for repair technicians. Manufacturers use software to digitally “pair” a specific part, like a camera or a screen, to the device’s unique serial number. Even if you swap in an identical, genuine part from another phone, the device’s software will reject it and disable features until it’s authorized by the manufacturer’s official software.

- Limited Access to Information: For decades, the official repair manuals, diagnostic software, and schematics needed to perform complex repairs have been treated as closely guarded trade secrets, available only to the manufacturers and their authorized service centers.

The Manufacturer’s Argument: The Other Side of the Story

To tell the full story, it’s important to understand why manufacturers claim these restrictions are necessary. They build their case on three main pillars:

- Safety and Security: They argue that allowing unauthorized repairs could lead to serious safety issues, like a poorly installed lithium-ion battery causing a fire. They also claim that giving broad access to diagnostic tools could compromise the device’s security features, like the facial recognition or fingerprint sensors that protect your data.

- Intellectual Property: They view their schematics and software as proprietary intellectual property and argue that releasing them would be giving away their competitive advantage.

- Quality Control: They maintain that the only way to guarantee a high-quality “user experience” is by controlling the entire repair process, ensuring that only genuine parts and certified techniques are used.

The Right to Repair Solution: The Growing Movement

The Right to Repair movement argues that these claims are often exaggerated to protect profitable repair and replacement cycles. Advocates are pushing for legislation that would grant consumers and independent shops several key rights:

- The right to purchase genuine parts and access necessary tools.

- The right to access repair manuals, schematics, and diagnostic software.

- The freedom to install custom software on devices they own.

This isn’t just a grassroots movement anymore; it’s a major legislative issue. Governments around the world are taking notice, and Canada is no exception, with federal and provincial bodies introducing and passing “Right to Repair” bills.

The Full Story: It’s About More Than Your Phone

While the iPhone is the most famous example, this fight extends everywhere. It’s about farmers being unable to repair their own John Deere tractors because of software locks. It’s about hospitals struggling with expensive repairs for critical medical equipment.

Ultimately, the Right to Repair is a debate about the nature of ownership in the 21st century. It connects your personal frustration over a broken phone to larger issues of corporate power, economic fairness, and the massive environmental problem of electronic waste. The choice is between a future of disposable technology controlled by a few large corporations, and a future where we have the freedom to maintain, modify, and truly own the things we buy.