You walk through a shopping mall, browse an airport terminal, or scroll through photos online. In each of these moments, a technology may be at work, capable of identifying you in a fraction of a second. This is facial recognition: a powerful tool that has quietly become one of the most contentious technologies of our time. It promises convenience and security, but at what cost to our privacy and fundamental freedoms?

The use of facial recognition in Canada has exploded into a major debate, pitting police and corporations against privacy commissioners and civil liberties advocates. This is the full story on what this technology is, how it’s being used, and the high-stakes battle to regulate it.

Part 1: What Is Facial Recognition and How Does It Work?

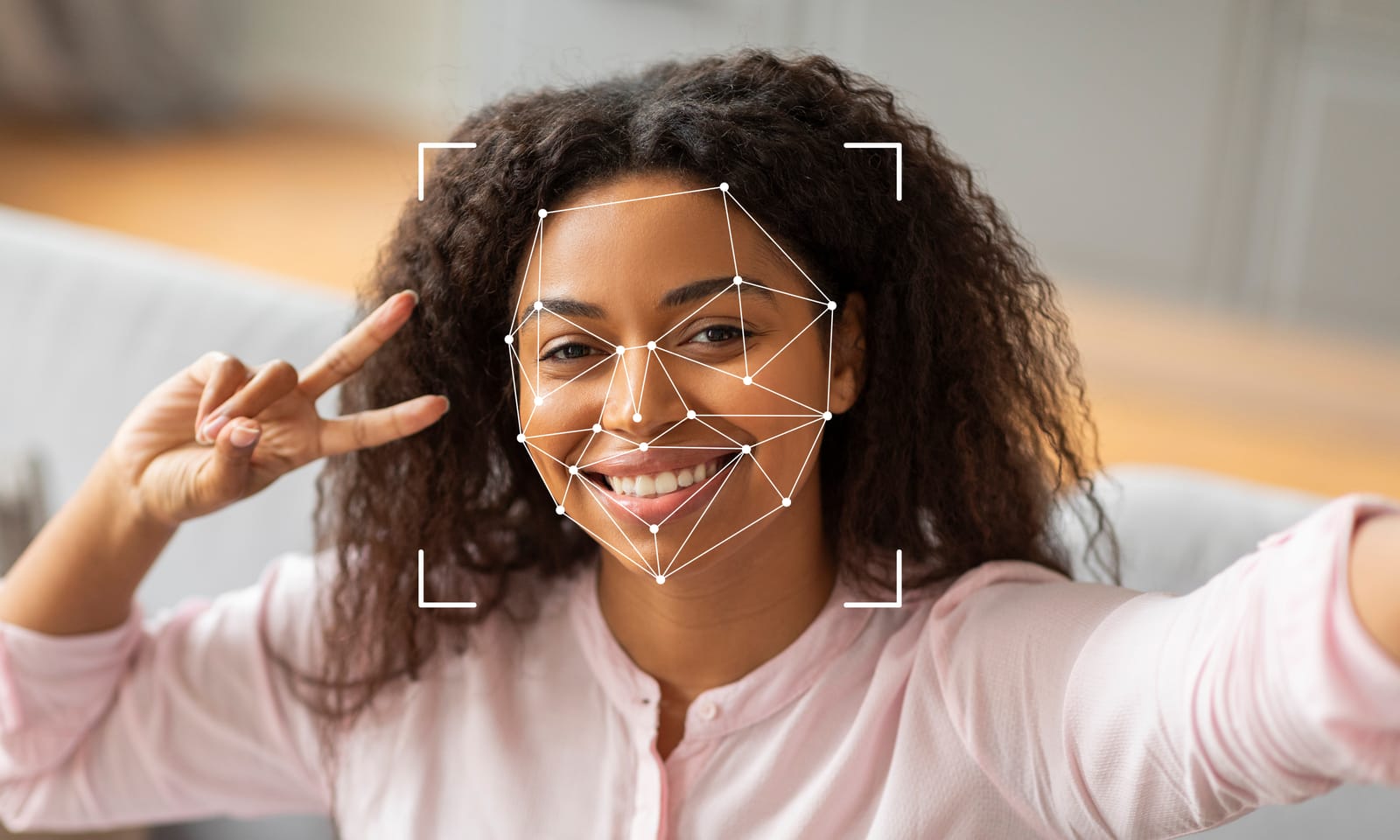

At its simplest, facial recognition is a way of identifying a person from a digital image or video. The software maps facial features to create a unique numerical code called a “faceprint.” This faceprint is then compared to a database of known faces to find a match. The source of that database is a critical part of the controversy.

A major concern is that the technology is not infallible and can be biased. A landmark study by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found that facial recognition algorithms were significantly less accurate when identifying people of colour, women, and the elderly. For example, some algorithms were up to 100 times more likely to misidentify an Asian or African American face compared to a white male face. This raises profound questions about fairness and accuracy, especially when the technology is used by law enforcement.

Part 2: The Flashpoint – Clearview AI and the RCMP

The most significant controversy surrounding facial recognition in Canada revolves around a single American company: Clearview AI. The company created a massive database by scraping billions of images of people from public websites and social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn—all without their consent.

In a series of scathing investigations, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC) delivered two landmark findings:

- First, the OPC ruled that Clearview AI’s scraping of images and the sale of its database to law enforcement constituted mass surveillance and was illegal under Canadian private-sector privacy law (PIPEDA).

- Second, the OPC found that the RCMP’s use of this technology was also a serious violation of the Privacy Act. The investigation revealed that the national police force had become a paying client of Clearview AI, using it for hundreds of searches without first assessing its legality or impact on the privacy rights of Canadians.

These findings, fiercely contested by Clearview AI but supported by privacy authorities across the country, established that using Canadians’ social media photos to build a police database was against the law.

Part 3: Not Just Police – Use in the Private Sector

The use of facial recognition is not limited to law enforcement. A major investigation by the Privacy Commissioner found that real estate giant Cadillac Fairview was embedding facial recognition cameras inside digital information kiosks in 12 of its shopping malls across Canada. The technology was used to analyze the faces of shoppers without their knowledge or consent to generate demographic data.

The OPC ruled that this was a violation of privacy law, as shoppers would not have reasonably expected their image to be captured and analyzed in this way. More recently, companies like Air Canada have begun rolling out facial recognition on a voluntary basis for passenger identification and boarding, showing how the technology is becoming more integrated into daily life.

Part 4: The Fight for Regulation and Rights

The Clearview AI scandal revealed a massive gap in Canadian law. While the Privacy Commissioner could rule the practice illegal, there was no specific legislation governing the use of this powerful technology. This has led to widespread calls for action.

- A Call for a Ban: Civil society groups like the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) have called for a ban on the use of facial recognition surveillance by police, arguing it is too dangerous for a democratic society.

- The Legal Framework: The use of this technology engages Canadians’ fundamental rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, particularly the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure.

- Proposed Guidelines: In response to the crisis, the Privacy Commissioner has issued guidelines for law enforcement, stating that a clear legal framework must be established by Parliament *before* police can lawfully use facial recognition.

The Bottom Line: An Unregulated Frontier

Facial recognition technology is advancing at a breathtaking pace, but Canada’s laws have not kept up. The country currently finds itself at a crossroads. The technology offers potential benefits for security and convenience, but it also poses unprecedented risks of mass surveillance, algorithmic bias, and the erosion of privacy.

The federal government’s new Digital Charter Implementation Act is a first step towards modernizing our privacy rules, but the specific questions raised by facial recognition remain largely unanswered. The outcome of this debate will be determined by the choices that citizens and their governments make now, and will define the balance between privacy and security for a generation.