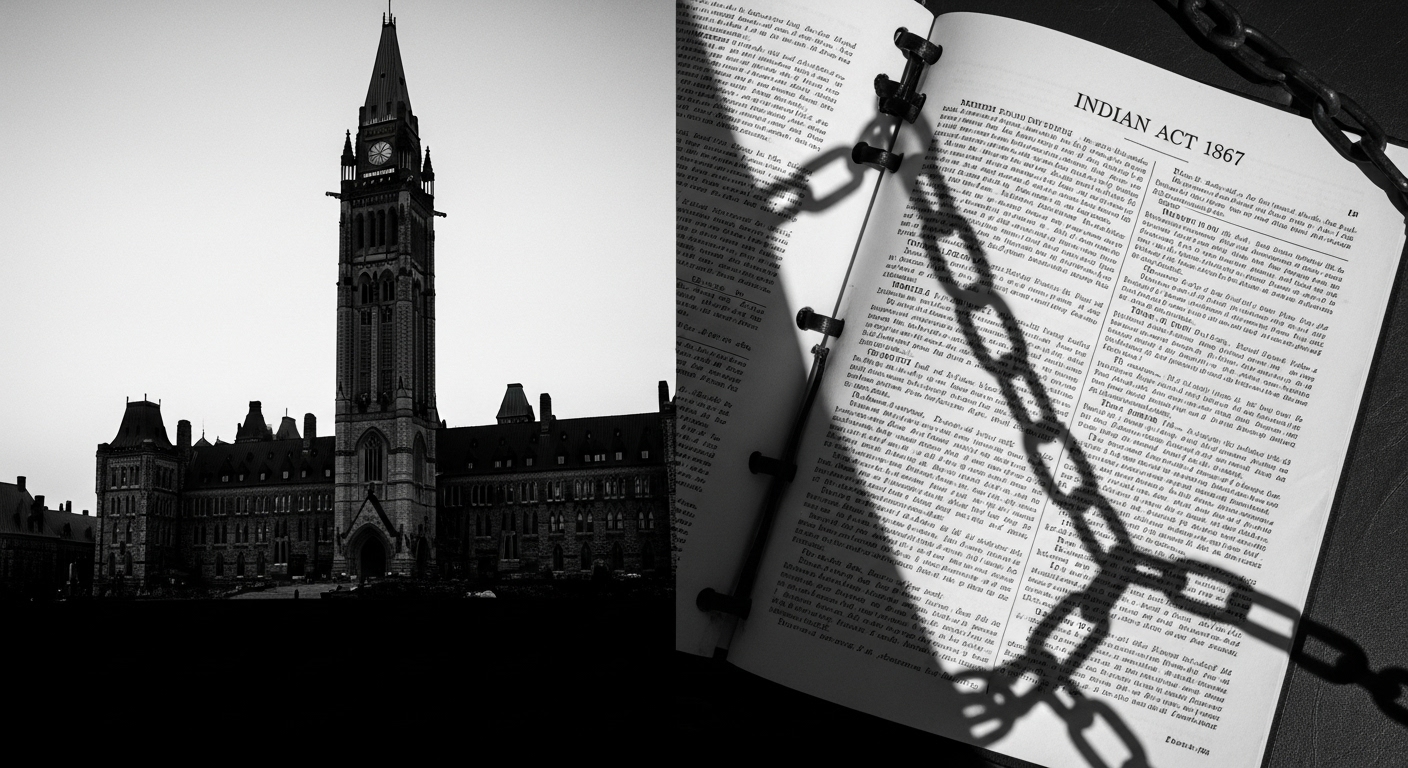

Few pieces of legislation have had a more profound and lasting impact on Canada than the Indian Act of 1876. Many Canadians have heard of it, but few understand what it is, what it did, and why it remains a central and deeply controversial part of the country’s legal landscape today.

This law has affected nearly every aspect of the lives of First Nations peoples for nearly 150 years. Understanding it is not just a history lesson; it’s essential for comprehending the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian state, and the modern pursuit of reconciliation. This is a plain-language guide to one of Canada’s most consequential laws.

Historical Context and Original Purpose: A Policy of Assimilation

The Indian Act was passed in 1876, consolidating all previous colonial laws regarding Indigenous peoples into one powerful piece of legislation. Its primary, stated purpose was assimilation. The goal was to control and forcibly assimilate First Nations by replacing their diverse forms of government, citizenship, and belonging with a singular, state-controlled system.

The Act was shaped by the colonial view that Indigenous cultures were inferior. It granted the federal government, through the Department of Indian Affairs, sweeping and paternalistic control over the governance, land, education, and cultural lives of First Nations, treating them as wards of the state rather than as sovereign partners. More information on this historical context can be found at The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Key Provisions of the Indian Act

The Act gave the federal government far-reaching powers. Some of its most significant provisions included:

- Definition of “Indian”: The Act established a rigid legal definition of who was an “Indian,” based on patrilineal descent. This overrode traditional kinship systems and was notoriously discriminatory, especially against women, who would lose their status for marrying non-Status men.

- Reserve System: It formalized Indian reserves—lands set aside for First Nations but held in trust by the Crown. The federal government retained ultimate control over these lands, limiting Indigenous autonomy and economic development.

- Band Governance: It imposed elected band councils, often replacing traditional and hereditary governance structures and excluding women from participating in politics until 1951.

- Cultural Restrictions: Later amendments banned vital spiritual and cultural practices, such as the Potlatch and the Sun Dance, in an explicit attempt to suppress Indigenous cultural life.

- Residential Schools: The Act provided the mechanism to compel First Nations children to attend residential schools, which were designed to erase their language and culture, leading to what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called cultural genocide.

- Enfranchisement: The Act included provisions to force or encourage First Nations individuals to give up their “Indian” status in exchange for Canadian citizenship and the right to vote.

A History of Amendments: From Oppression to Equity

The Indian Act has been amended many times, often in response to legal challenges and powerful advocacy from First Nations leaders. Key amendments include:

- 1951: This major revision removed the most severe cultural bans and restrictions on movement. However, it also introduced new discriminatory rules, such as the “Double Mother” clause.

- 1985 (Bill C-31): A landmark amendment that, in response to international human rights challenges, sought to remove gender discrimination. It allowed women who lost status through marriage to regain it, along with their children, and eliminated forced enfranchisement.

- 2017 (Bill S-3): This bill was the most recent major effort to address and eliminate all remaining sex-based inequities in status registration, a process that is still ongoing. For an official overview, see the Government of Canada’s summary page.

Lasting Impacts: A Legacy of Harm and Resistance

The effects of the Indian Act have been devastating and continue to be felt today. The policies of assimilation and control have led to cultural erosion, social disruption, economic marginalization, and profound intergenerational trauma. However, the story of the Indian Act is also one of unwavering resistance. From the very beginning, First Nations have challenged its legitimacy and fought to maintain their cultures, languages, and right to self-determination, as detailed by resources like UBC’s Indigenous Foundations.

The Path Forward: Self-Government and Reconciliation

Many Canadians wonder why such a widely condemned law still exists. The answer is complex. The 1969 “white paper” proposal to abolish the Act was met with fierce resistance, as it was seen as yet another attempt at assimilation under a different guise. For many First Nations, the Act, despite its deep flaws, is the primary legal document that defines the unique relationship with, and responsibilities of, the federal government.

Unilaterally repealing it without a negotiated alternative could create a legal vacuum. Therefore, the modern approach is for Nations to transition out from under its authority. The ultimate goal is to replace the control of the Indian Act with their own laws and constitutions, a process known as Indigenous self-government. This aligns with the Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples, which is based on the recognition of rights and self-determination.

Conclusion

The Indian Act of 1876 is a complex and controversial piece of legislation that has shaped Canada’s relationship with First Nations for nearly 150 years. Its original aim of assimilation led to policies that caused significant harm. While amendments have addressed some discriminatory aspects, the Act remains a symbol of colonial control. Understanding its history and legacy is crucial for all Canadians seeking to engage with reconciliation and support the restoration of Indigenous control over their lands, cultures, and futures, echoing the powerful sentiment, “nothing about us without us.”